A Time for Foolishness

Working with the uncertain and sensing the emergent has always meant starting before we’re ready. It means experimenting, being prepared to be wrong, and change direction. It means, sometimes, being willing to look foolish.

There is an essential difference between being foolish and being stupid. Stupidity is a kind of surrender, the quiet acceptance of whatever authority hands down, free of curiosity or doubt. Foolishness is something else entirely. The medieval fool was not an idiot but a practitioner of perspective, someone licensed to speak truth to power through humour, irony and play. The fool lived at the edge of the court, saying what others could not, and revealing the cracks in certainty. Stupidity is passive; foolishness is a craft. One narrows the world, the other opens it.

Foolishness is living at the edge of things, trespassing past boundaries to spot what is moving towards us. I have spent a career as a fool, and wouldn’t change a moment of it, perhaps other than developing a better sense of timing. Being right after the event might lend a moment of satisfaction, but it doesn’t achieve as much as a well-timed intervention.

Foolishness needs an awareness of Kairos time as much as Chronos; using the right words and examples at the right time. The fool’s role was never to humiliate the powerful, but to help them see what they could not admit. Sun Tzu advised building a golden bridge for those who are being proved wrong, a dignified path back from a weak position. In that sense, the modern fool is a strategist as much as a truth-teller. Surfacing uncomfortable realities with humour and grace, while offering a safe route towards a better stance.

The craft lies in revealing the truth without forcing anyone to cling to a failing story.

My entire career, half a century of it, has seen the world of work analysed, systematised, and designed for performance that has promoted shareholder primacy and Milton Friedman’s view that "The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits." He argued that a corporation’s primary responsibility is to its shareholders, effectively making profit maximisation the corporate goal.

Yet, despite its obvious moral and practical flaws and half a century of challenges, the logic of shareholder primacy still sits stubbornly at the centre of corporate life. Legal scholars such as Lynn Stout showed that the doctrine was never a legal obligation in the first place, but only a habit born of convenience, amplified by business schools. Economists like Joseph Stiglitz demonstrated how a narrow focus on shareholder returns accelerates inequality, undermines long-term investment and weakens the productive base of economies. Strategists from Michael Porter onwards reframed social and environmental concerns as competitive advantages rather than distractions. Even investors such as Paul Tudor Jones have pointed to the social wreckage created when short-term profit is treated as a governing principle. And yet the idea endures. Boards still behave as if Friedman’s dictum were carved into company law. Incentive structures, quarterly reporting cycles and cultural norms keep pulling leaders back towards the same thin interpretation of corporate purpose. We now have decades of evidence that the doctrine distorts behaviour, degrades resilience and creates risks that accumulate invisibly until they erupt. But habits, once embedded in institutions, take far longer to fade than the arguments that undermine them.

Telling the truth to power requires a strategy if the Fool is not to leave by the window rather than the door they came in through. Those we work with are rarely stupid; they often have a well-developed sense of what we help them see, but cannot articulate it to an audience that won't like it. More often than not, the Fool must be prepared to accept the blame. It’s part of the job.

The Fool as Alchemist.

Having spent two months, starting before I was ready, and exploring with you what I was sensing, it is time to share my own Foolish thoughts on where I think we might take the idea of The Athanor; how we might take what we find in the ashes of the workplace that is disintegrating to shape something rather more human, satisfying, generous and, using the word advisedly, beautiful.

My Foolishness is my own, and comes in three parts. First, a view on how I am sorting through the ashes of the disappearing workplace; Second , what I am exploring in the emerging workplace; and Third, The Athanor as container - how I turn what I find into something valuable.

A Foolish View

Work, whatever its form, is ultimately a human activity, and whilst what we can measure has enabled massive improvements in process and profitability, it does not touch what makes it meaningful. Foolishness comes at work from the standpoint of the individual, to consider how the organic input matter of work, us, meets the inorganic output, profit.

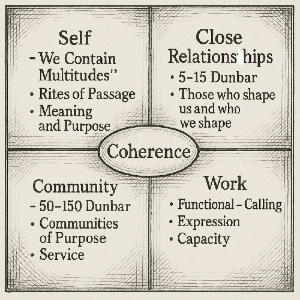

At the heart of the view is our relationship with work. I have considered several terms, and have settled, for now, on the idea of coherence - our sense of ease when it comes to how we relate to ourselves, our surroundings, and the elements that comprise our work.

I am considering four overlapping boundaries. Over the coming weeks, I want to explore these spaces to understand how we retain our autonomy in a world that would rather control us, how we connect with the possibility we represent, and how we might make the contribution we are here to make.

Our relationship with ourselves. (#self)

As Walt Whitman wrote in “Song of Myself”.

Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

It feels appropriate. We are asked to play so many roles, in so many different contexts. We are expected to be efficient and creative, to follow process and improvise, and to be loyal and committed whilst accepting our disposability. We are pulled in so many directions; as employee, employer, spouse, lover, parent, grandparent, colleague, teacher, student and citizen. It feels as though schizophrenia has moved from pathology to qualification. How do we make sense of these conflicts?

Our relationship with those closest to us (#closest)

A handful of people shape us, Dunbar says five, others say 8, that we spend the most time with. They change our lives, and we can see and feel their presence in the work we do today. At one time, we would find them at work, but that is less and less the case as the workplace fragments. As the world changes, choosing those who shape us is an integral part of our strategies and cannot be left to chance. It is a paradox that as work demands more and more of us, we sacrifice these relationships to the urgency of things that are much less important.

Our Tribe (#tribe)

We are tribal animals, and cannot hold meaningful relationships beyond around 150 others, no matter how we use technology. It can give us connections, but not relationships. Relationships are far more profound and fragile. Our 150 determine where our closest relationships come from, our sense of the world, the boundaries we choose to work within, and the quality of our networks, which are shaped by our histories, our genetics, and circumstances. We have more ability to choose our tribes than at any point in our past, and, as with our closest relationships, they are vital, and we need to consider them carefully.

Our Work (#work)

If we have more choice than ever before regarding our tribes, we have ever less with our work. Globalisation and technology were meant to open doors, yet they seem to have narrowed the path for many people. Competition is now global, so the old vertical ladders inside firms have fewer rungs and far steeper expectations. Technology has made work cleaner and more efficient, but it has also stripped out the messy, developmental tasks that once helped people grow. At the same time, whole sectors have consolidated into a handful of large employers, which means that moving sideways has become harder unless you are in one of the favoured digital or professional fields that attract global demand. The result is a labour market that looks busy on the surface yet feels strangely static, with plenty of churn but little real progression.

The result is work has changed from somewhere we could develop our professional identity to something altogether more transactional and opportunist. Whilst the reality is that whilst we have only ever been role tenants if we work for others, we are now more like sharecroppers, measured by the our output in the moment. Our professional identity is our responsibility; it cannot be outsourced, and the balance between what we learn at work, and what we learn outside it has changed. Whether we like it or not, we are all self-employed.

Foolish Exploration

John Muir wrote in 'My First Summer in the Sierra; "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” I know how he feels.

However, I need to start somewhere, and these are the areas I am going to focus on until they point me somewhere else:

Uncertainty (#uncertainty). This is perhaps the core theme of the present, as the way we thought the world works seems to dissolve. Understanding uncertainty is not only the key to taming our fear, it is also the source of what we need to know as we come to terms with what is emerging.

Craft (#craft). Craft is at the heart of our relationship with our work. It is our signature (I made this), the source of our learning as we shape what we are given into something valuable that will outlast us, and our path to Mastery of what matters to us.

Networks (#networks). The networks we are part of determine the people, ideas and resources we are connected to, how we influence them, and the impact we have. Networks not only carry information, but also determine where it gathers and collects until it has enough mass to change the network itself; how we think about networks matters.

The Athanor (#athanor). When we're working at the edge of what we understand, we cannot rush. The Athanor is a container where we use the energy of conversations to convert uncertainty into inquiry, and inquiry into action. How we meet, how often and the quality of our conversation. How we entertain trust, conflict and the unexpected shapes and what we discover from them.

As Otto Scharmer, author of "'Theory U', tells us "The quality of the results depend on the quality of the container, the holding space we create for each other".

My Laboratory

Agriculture is one of the most useful laboratories we have for understanding the nature of organisational change. If alchemy is the art of stewarding transformation under uncertain conditions, then farming has been practising it for millennia. It works with living systems that never quite behave, with vessels that leak, with forces that cannot be negotiated with, and with outcomes that only emerge in their own time. Most organisations imagine change as an engineering problem; agriculture treats it as cultivation.

I have no background in farming, yet it has long been a subject of professional fascination for me. My day has started, for over twenty-five years, with "Farming Today" on BBC Radio 4 at 05:45. I find it gives me context.

What makes farming so instructive for me is its humility in the face of complexity. Weather, soil, biology, markets and policy all interact in ways no plan can fully contain. Decisions are made with incomplete information. Feedback arrives slowly and often comes disguised. In that sense, farming lives permanently in the alchemical nigredo, dark soil where old assumptions break down, and new possibilities take root.

Crucially, agriculture works through precursors. Farmers do not act directly on the harvest; they act on the conditions that make a harvest possible. They improve soil, rotate crops, tend boundaries and encourage pollinators. Most change efforts fail because they try to force fruiting rather than cultivate it, and when it is forced, there are often unintended, long-term consequences. Other organisations would do well to notice this

Agriculture also shows the importance of small groups and tacit knowledge. Small teams run farms, whether family-owned, corporate, or tenanted. Whilst there is increasing formal education, apprenticeship, and communities of practice, slow, cumulative craft remains vital, and it reveals the dangers of sterile abstraction, when scale and metrics displace judgment and resilience.

Most other organisations, no matter how uncertain they think their environment is shaped by competition, regulation and circumstance, can learn from farmers. Farmers face the realities of man-made events like climate change, the vicissitudes of weather, geopolitics and limited resources, because not only do we not make land anymore, we are destroying it even as the population that needs to be fed increases.

So, given the importance of boundaries when focusing, agriculture is my laboratory. Just about every other organisational challenge I can think of is reflected there.

Your Laboratory

...and your processes will be different.

One of the core purposes of The Athanor is to learn from each other as we each find our way at the edges of what we do. I hope some of what I write here is useful, but it is only a perspective, not the truth. What matters is when we bring our individual uncertainties, perceived truths and experiences together and apply the energy of open, curious, generative conversation and challenge to what we are noticing.

And so, we start

October and November have been an orientation exercise; now it is time to start. December will be a transition month, when the important things of life have priority: family, friends and gratitude.

Our open conversations will be there for any who want to join, at 5:00pm UK time on 3rd, 10th and 17th December, and then a break until 10th January. I will continue to post during the period, because change never stops.

Here is the Link for those who want to join:

Comments ()