Going Freehold

I realised I was a renter when my blog host locked me out of my email list.

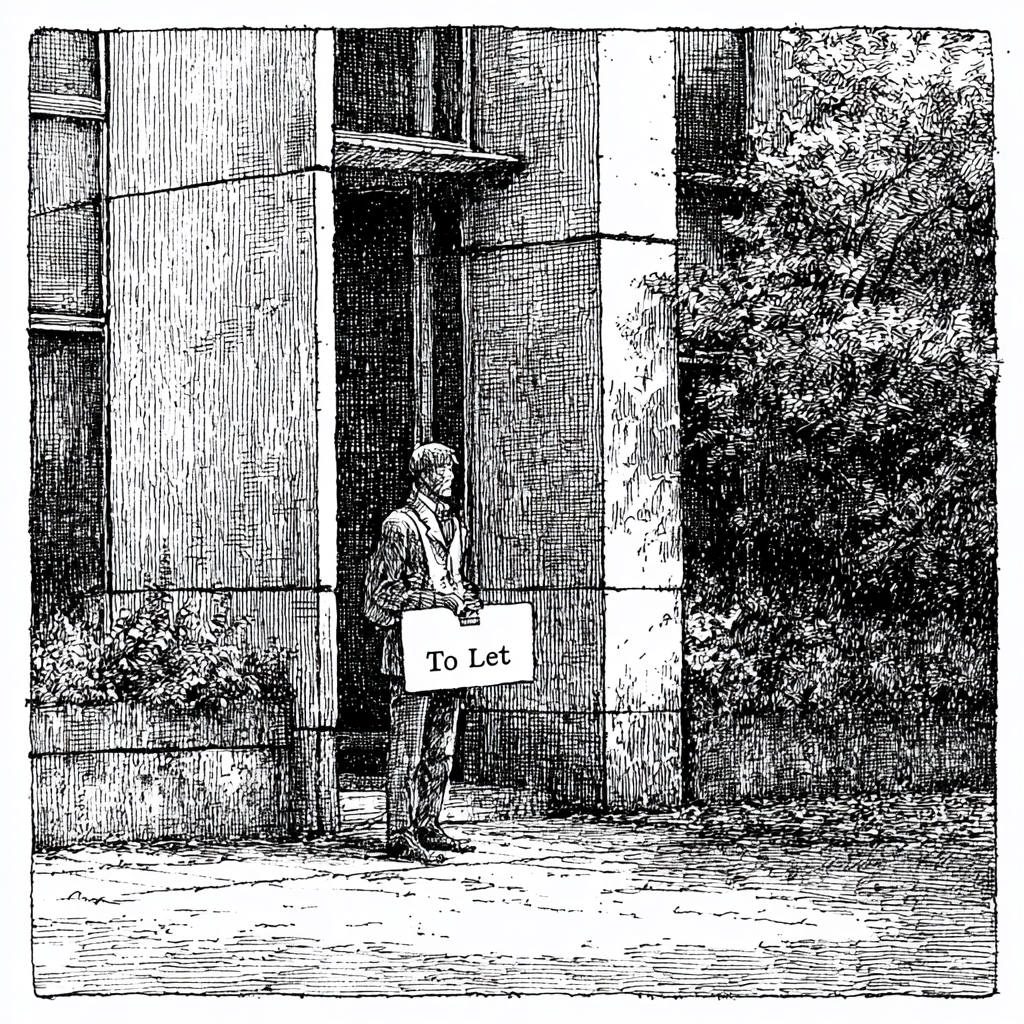

Nothing dramatic, just an authentication requirement before I could contact my own subscribers. Sensible policy, rather clunky execution. But the moment crystallised something I’d been circling: I don’t own this platform. I rent space inside someone else’s walls. Substack, Ghost, Medium, whatever comes next, I’m a tenant, not a freeholder. I’m building their platform equity faster than my own personal equity.

The moment I saw one landlord, I saw them everywhere, in our cars, software, phones, entertainment, and energy. We rent our cars through subscriptions, our software through SaaS, our entertainment through streaming services, our energy through utilities we don’t control. The list extends further than we typically notice. It’s convenient, efficient, and investors love it. Annual recurring revenue makes balance sheets predictable.

Some landlords are excellent. What separates them from the extractive sort is the nature of their relationship. If your landlord looks you in the eye, participates in your community, or connects beyond the transaction, it’s different. The trouble is that most of us have no idea who our digital landlords are, what their strategies are, or our place in them. When eviction is a profit opportunity for the unscrupulous, the difference matters.

Not many generations ago, my forebears experienced enclosure firsthand. The common land they farmed was enclosed in the 18th and 19th Centuries, and what they thought was theirs no longer was. A rude awakening, as out of necessity, they either worked for new landlords or migrated to the industrialising cities.

Where they faced enclosure, we face what Cory Doctorow calls enshittification. Platforms begin by delighting users, pivot to pleasing business customers, then squeeze both to feed shareholders. It’s a familiar decay curve: abundance to scarcity, participation to extraction. Doctorow’s cure isn’t better platforms, it’s better power distribution through small, interoperable systems that restore agency to those who create and use them. I think he has a point. What do we do about it?

Who Will We Become?

In This is Strategy, Seth Godin offers a particular definition:

“Who will we become?

Who will we be of service to?

And who will they help others to become?”

Powerful questions. Yet according to the ONS, approximately 87% of us are employees. If we work for someone, our agency is constrained in answering these questions. The bigger the company, often the more we’re paid, and the less choice we have—unless we reach the Board and escape velocity. Even then, we likely find ourselves with new landlords in the shape of shareholders.

We face a constraint: for the vast majority, particularly in early careers, employment is necessary. As employees, we’re expected to be “productive” on terms set by others, and before we know it, walls close in on our expectations of ourselves. We stay within job descriptions, running faster to stand still, while those behind us enter the same role and catch up more quickly than we progress.

At some point, given cheaper people and more capable technology, our costs no longer generate enough value to pay the rent.

Preparing for Transition

If we know this point will arrive, we can prepare for it. It means doing the equivalent of saving for a deposit on the next stage of our careers. (We can hope to earn enough in the first stage to make the second irrelevant. But the odds aren’t in our favour.)

Going freehold is a strategy. It involves reducing the number of landlords we depend on and choosing them more carefully. Paying attention to where our careers actually “live” - our careers, like us, become the average of the ones they keep company with the most. We must recognise what our inner voice whispers, and respect the power of things that annoy us as pointers to growth. (a nod here to a brilliant post by Experimental History)

In the end, we are all searching for places where our uniqueness can thrive, to our benefit and those we serve:

“The things to do are: the things that need doing, that you see need to be done, and that no one else seems to see need to be done. Then you will conceive your own way of doing that which needs to be done—that no one else has told you to do or how to do it.”

— Buckminster Fuller, Letter to “Michael,” 16 February 1970

What Going Freehold Actually Means

Going freehold isn’t about rejecting all platforms or becoming completely self-sufficient. That’s neither possible nor desirable. It’s about strategic coherence in how we build agency within constraints.

It means developing capabilities no platform can revoke. Building direct relationships that survive when intermediaries disappear. Creating assets, knowledge, networks, reputation, skills, that belong to us regardless of who controls the infrastructure.

Most critically, it means shifting from optimisation to resilience. The highly optimised career path is fragile. It assumes the current game continues. When rules change, optimised systems break catastrophically. Resilient careers maintain sufficient variety not just to adapt, but to thrive as the surprises arrive.

When the pressure is on, and uncertainty abounds, owning something small is less precarious than renting something big and flashy because, in the end, it's the craft that creates the connection, and the content that does the work. The showroom, the offices, and the platform are little more than ego.

This isn’t easy. Not much that matters ever is.

The Athanor as Laboratory

I’ve created The Athanor as a separate space for people working through these questions together. It’s not a solution, it’s a craft workshop where explore boundaries and run meaningful experiments in each other's company.

It won’t tell you how to live your career; rather it will enable what we will do together (explore these questions in the company of others doing the same work).

If you recognise the pattern; if you’ve felt the walls closing in, or wondered whether you’re building someone else’s asset more than your own, then the work is finding your own way through. Not following someone else’s plan, but developing your own strategy for going freehold.

That work happens best in the company of others attempting the same thing.

Have a great weekend

Comments ()