When the Quiet Disappears

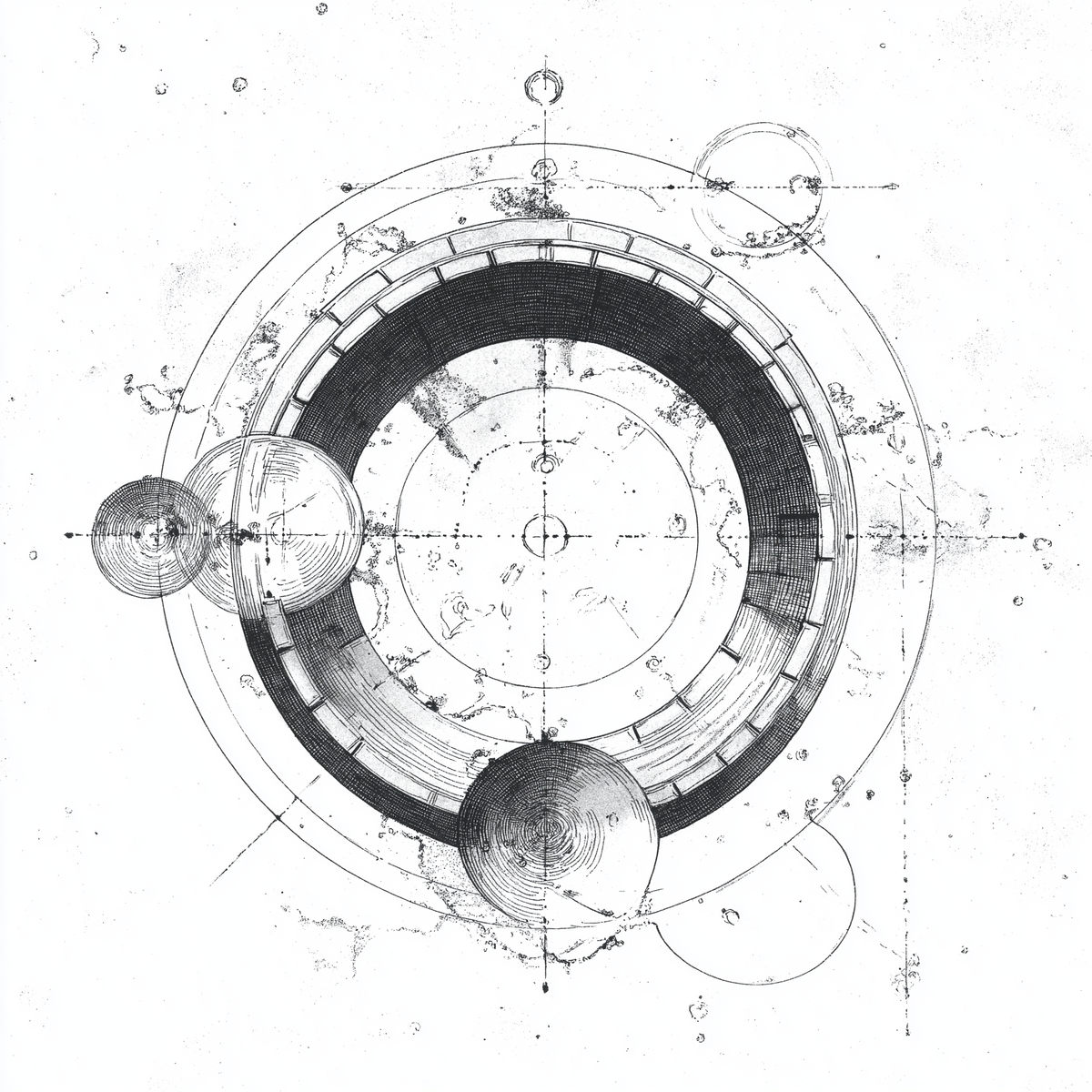

Working with spheres of influence.

When the quiet before that shapes the events about to happen gives way to noise, it does so suddenly. All the things that we are now getting excited about seem obvious in retrospect. So why didn't we see them?

There is nothing in Donald Trump's actions over the last few days that should surprise us. It appears that, under U.S. law, Trump has not committed any illegal act. The style may have offended our sensibilities, but, according to Edward Stourton in the Guardian, all the indications are that this is merely a continuation of American interests of the last century.

We have started 2026 by rolling the clock back 150 years to ideas of the Great Game and Spheres of Influence.

The message is clear: might is right. Over the course of the weekend, we find ourselves in a Thucydidean world of "the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must". What has long been evident in the quiet is now visible.

In many ways, it falls under the remit of radical uncertainty. Like black swans, the evidence is there, and we can be reasonably confident it will happen. It's just that we don't know quite when, and quite where.

Now we do, and we best adapt.

I'm not going to add any more noise to the volume of political comments. My thoughts are on the effect this change will have on the dominant mindset in business, and the implications for those who do the work.

This week has seen "Might is Right" as a strategy legitimised across every domain. In cultures where leaders love to mimic military language, no matter how inappropriate, we can expect to see MiR echoed to legitimise what is already leadership practice. From technology to pharmaceuticals, to any other area where large corporations dominate, I expect to see any veneer that has previously been overlaid to make dominance somehow more respectable peeled away.

What has been a veiled practice seems likely to become open practice. A line used by a previous Republican president, "If you're not with us, you're against us," is likely to reappear, and if you're with us, you'll do as you're told.

I wrote in a previous post about the stages that conversations go through. MiR is the new embedded certainty: we have a view of the world, we are certain we are right, and it's working. Along the way, in ways we cannot yet see, it will begin to fray at the edges, a process I termed anomalous friction. We will attempt to deal with it through assertive processes; Agile and Lean Six Sigma with updated names, as we eliminate outliers to make the model we think is "perfect" function properly. Inside the organisation, however, there will be an increasing sense of private disquiet, the sense that the friction is chronic and signals something very real. The sort of thing that we can't talk about openly, because it would put us on the edge and expose us to ridicule or worse.

There comes a point, though, where private disquiet gives way to shared naming. We begin to talk to each other quietly in corners until enough momentum builds that we find ourselves reframing our reality, reframing and reorienting,

If you're in the tech industry right now, I suspect you're orientating with a vengeance as the foundation upon which you've built your job disappears, partly to AI, partly to the idea of AI, and partly because of the money those with no real idea of how to use it need to fund it.

Of course, it's not just AI. Any sector in which the primary driver is short-term returns is subject to the same pressure. We are seeing it in every sector, from education and healthcare to professions whose circumstances have changed out of all recognition in the time it takes to train to be part of them.

Whether we're inside the walls, reluctantly reinforcing them for those who own them, or outside them, wondering where to go next, the world has changed for us, and we must adapt.

We find ourselves beyond private disquiet, our concerns confirmed as we name them together, and seeking ways to reframe, reorient, and decide what to do next. That's the intent behind our conversations on Wednesdays, and if you want to join us, you'll find a link at the end of this post.

How might we think about the space we find ourselves in?

As a starting point, I looked at who thrived the last time the world found itself in a "Might is Right" paradigm, the period defined by the "Great Game" and "Spheres of Influence", when British Hegemony was at its height (and a cautionary note to those who are revelling in their military might; throughout history, the tipping point of failure has been when countries have become empires. The cycle will not be denied.)

Those who thrived in the Great Game were the Edge Dwellers, the intermediary traders and merchants who understood and developed the networks that spread like mycelium between the centres of power. Small states with strategic geography thrived; able to punch above their weight by where they were.

In a timely reflection, during the Great Game, Uruguay thrived by positioning itself as a buffer between the Argentine and Brazilian spheres, which were plainly opposed to each other. Panama's location made it invaluable, regardless of who controlled the canal, by making it necessary to the dominant power's strategic architecture while remaining too costly to fully absorb.

Specialised service providers thrived: insurance companies, shipping firms, telegraph operators, and newly emerging banks that facilitated sphere of influence economics. They thrived because spheres of influence require infrastructure for extraction and control, and dominant powers often prefer to outsource these functions rather than develop them directly. )Today, the USA's emerging relationship with Venezuela will be interesting to watch.

Technology has changed the nature of the edges, but not, I think, the principles. We do not yet know what the rules will be, just as it was unclear during the Great Game period. I anticipate that platform translators who can bridge competing AI ecosystems will be important. Imagine that the spheres of influence will fragment around Chinese, American, and potentially European architectures, and those who can operate across these boundaries will hold positions of significant influence. It won't just be technology. There will be epistemic brokers, perhaps a version of digital diplomats.

I can imagine the importance of verification specialists who validate AI outputs in areas where errors are particularly sensitive and context matters. AI will be good at a lot of things, but not relationships. It doesn't have intuition; it is not embodied, and is, as Iain McGilchrist might say, "A wonderful emissary, but a dreadful master."

I think context architects will be important: strategists who design the vessels within which AI operates effectively. Not prompt engineers, but people who understand how to structure problems, frame questions, and establish guardrails so that algorithmic processing serves genuine inquiry rather than replacing it.

And lastly, but close to my heart, I think there will be enclaves that explicitly reject algorithmic substitution in domains where clients value human judgement precisely because it's not scalable. They will thrive not by competing with AI but by occupying positions where AI substitution would destroy the value proposition.

So, as those high on the drug that is efficiency and productivity salivate over the short-term prospects of AI, ignoring the complexities that will affect its longer-term development, I think the pattern will be that those who can operate in the gaps and seams and across boundaries will find themselves not just important, but also powerful.

Not at scale, perhaps, but Machiavelli didn't scale, yet he certainly made an impact.

These are my thoughts on some of the roles that might emerge as the comfortable organisational chart world we have inhabited for so long dissolves. You all have your own ideas, and the fun is in sharing those together to see what we notice.

Zoom will be open on Wednesday night at 5 o'clock UK time. (And for those of you in time zones far, far away, I'm looking at an additional one that is more convenient for you)

If you can make it, we'd love to see you.

Comments ()